The Abbey-Principality of San Luigi and its dependent communions wish everyone a very happy Christmas.

The Abbey-Principality of San Luigi and its dependent communions wish everyone a very happy Christmas.

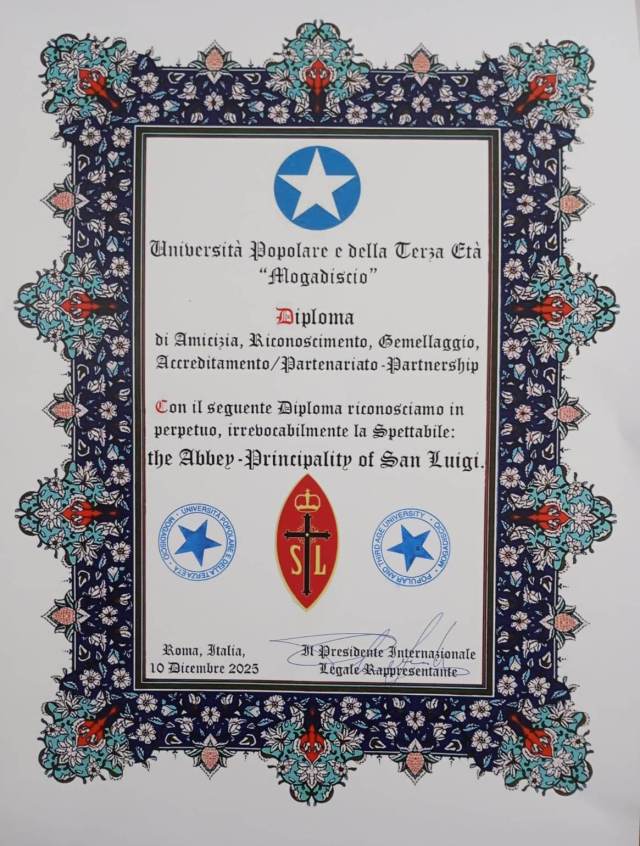

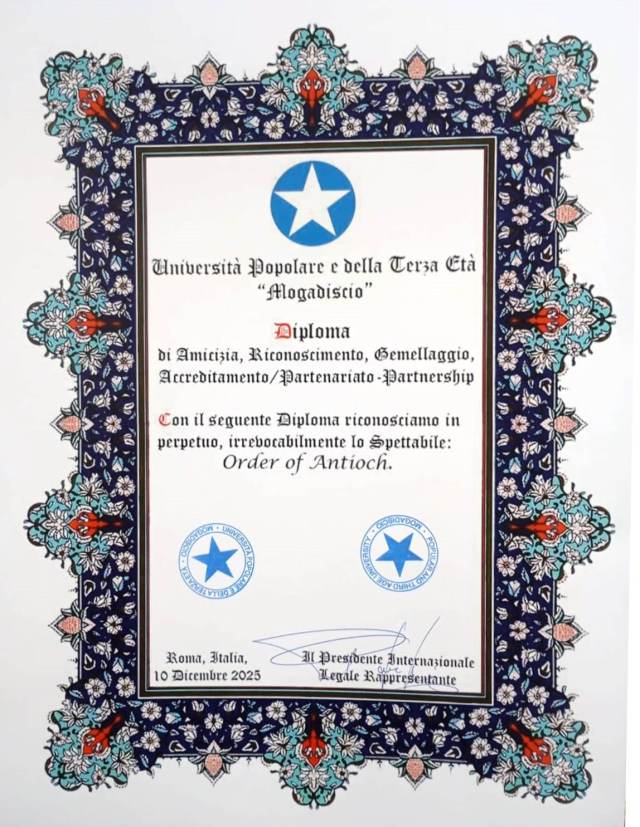

The Università Popolare e della Terza Età “Mogadiscio” is a private university in Rome, Italy, registered with the government authorities in December 2025. It is in the Italian tradition of “popular universities” and “universities of the third age”, a special category of universities in Italy that are concerned with instruction and research pursued purely for academic, religious, social and cultural benefit.

The University has issued a Diploma of Friendship, Recognition, Twinning, Accreditation and Partnership to the Abbey-Principality of San Luigi, in perpetuity.

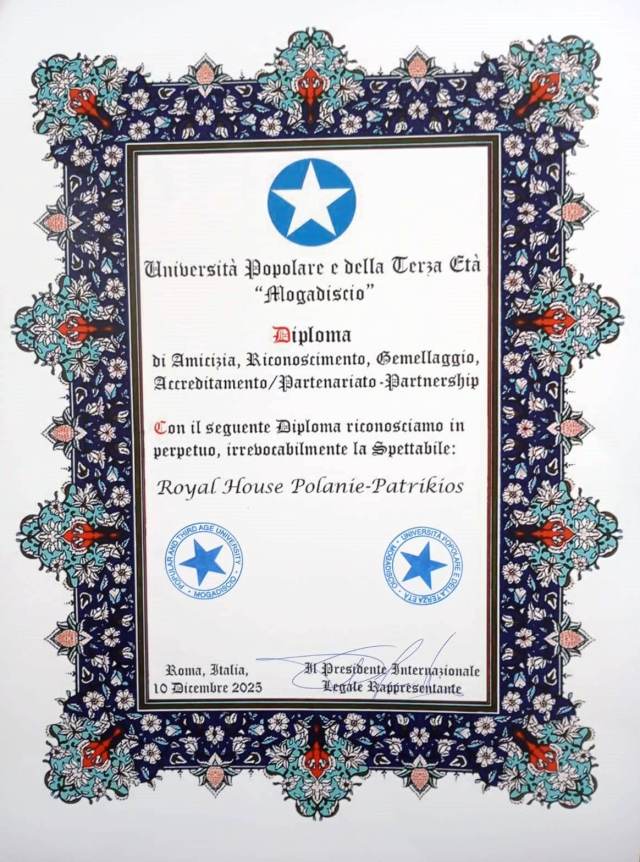

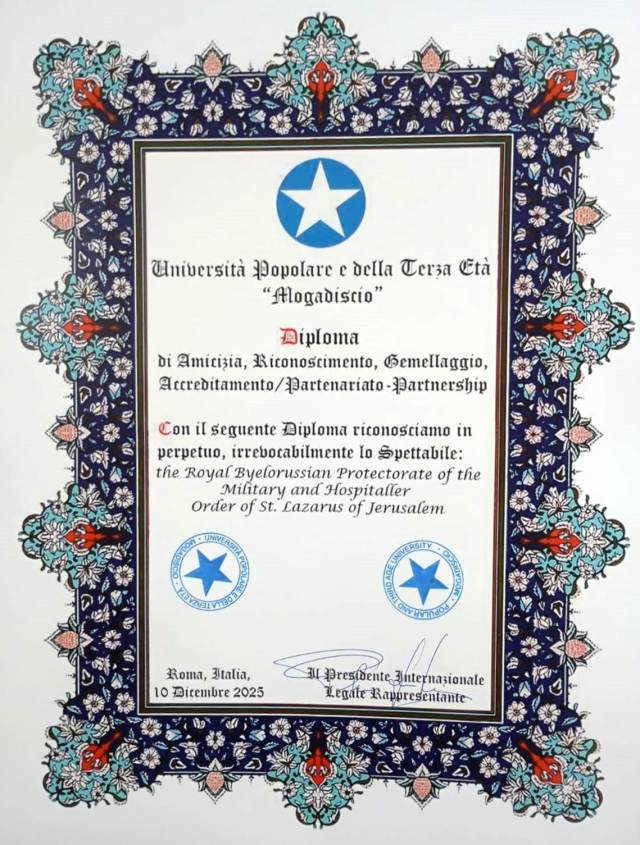

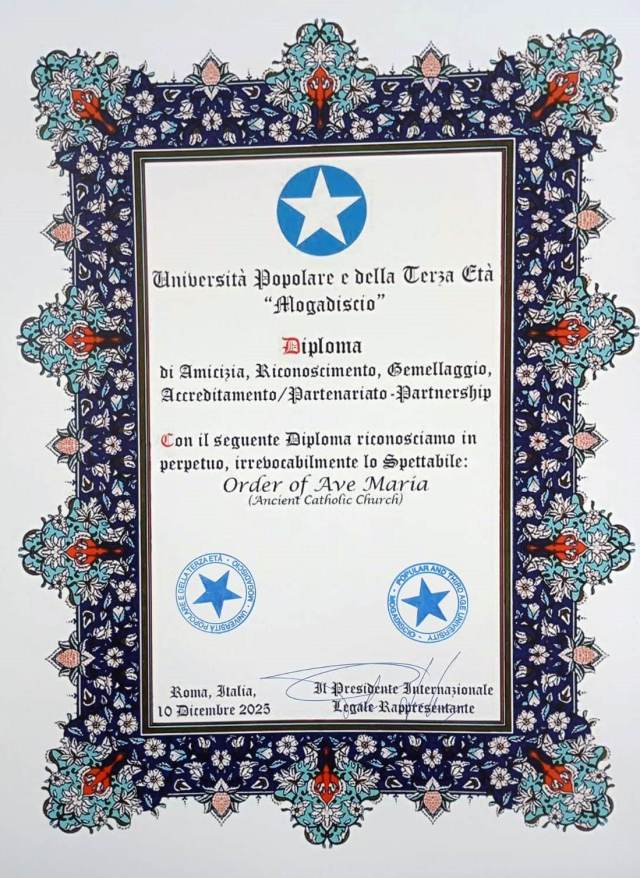

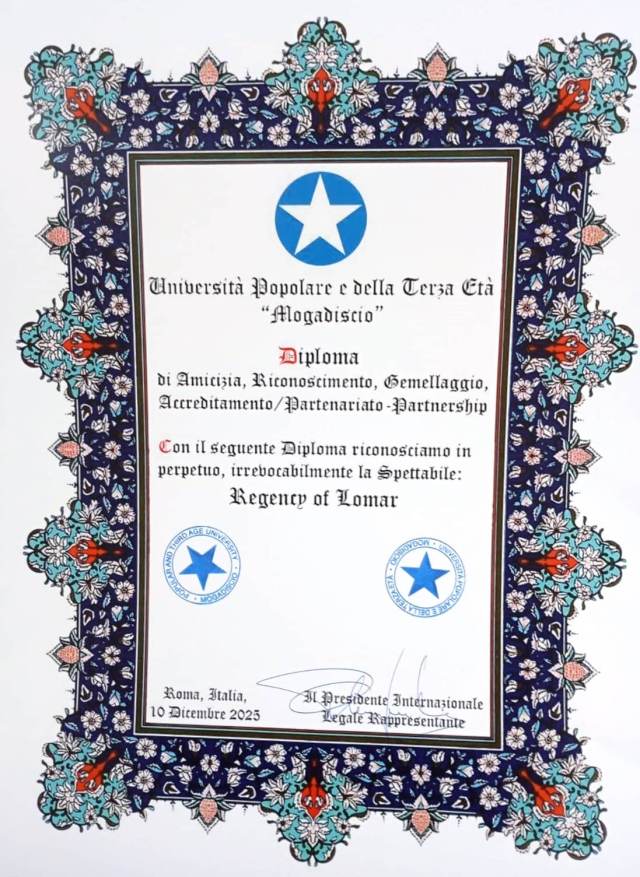

The University has also issued diplomas of friendship, recognition, twinning, accreditation and partnership to the following institutions of the Abbey-Principality:

The Constantinople Orthodox Institute

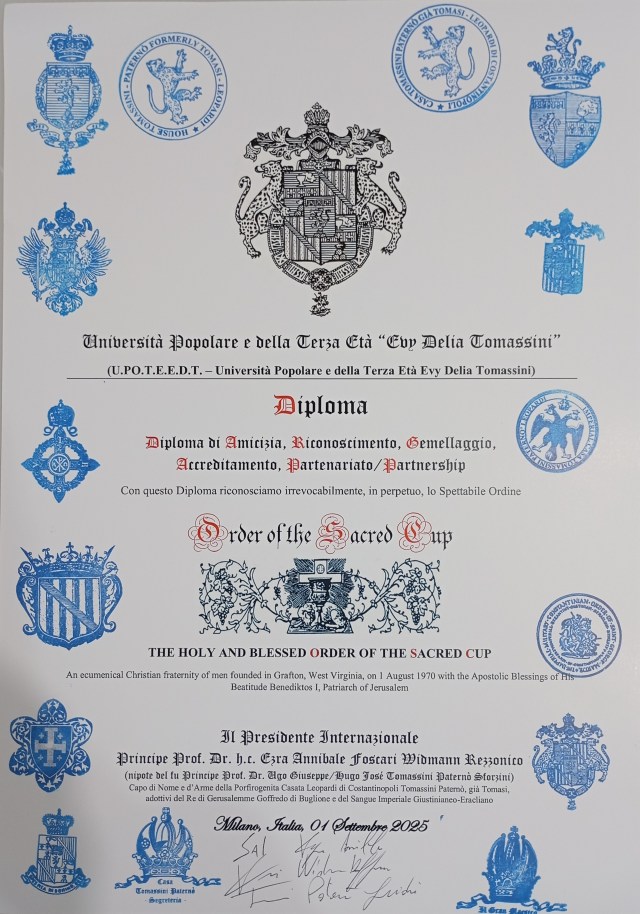

The Order of the Sacred Cup

The Royal Byelorussian Protectorate of the Order of St Lazarus

The Belarus Monarchist Association

The Order of the Crown of Thorns

The Anglican Association of Colleges and Schools

The Order of Corporate Reunion

The Royal House Polanie-Patrikios

The Royal Byelorussian Protectorate of the Order of St John

The Order of Ave Maria

The Regency of Lomar

The International College of Arms of the Noblesse

The Order of the Holy Wisdom

The Institute of Arts and Letters (London)

The Epiphany Guild

The Ecclesia Apostolica Divinorum Mysteriorum

The Apostolate of the Holy Wisdom

The Order of S. Teresa – The Little Flower

The Grand Prix Humanitaire de France et des Colonies

The Prefectory of Great Britain of the Confraternitas Oecumenica Sancti Sepulcri Hierosolymitani

The Catholicate of the West

The Order of the Lion and the Black Cross

The Order of Antioch

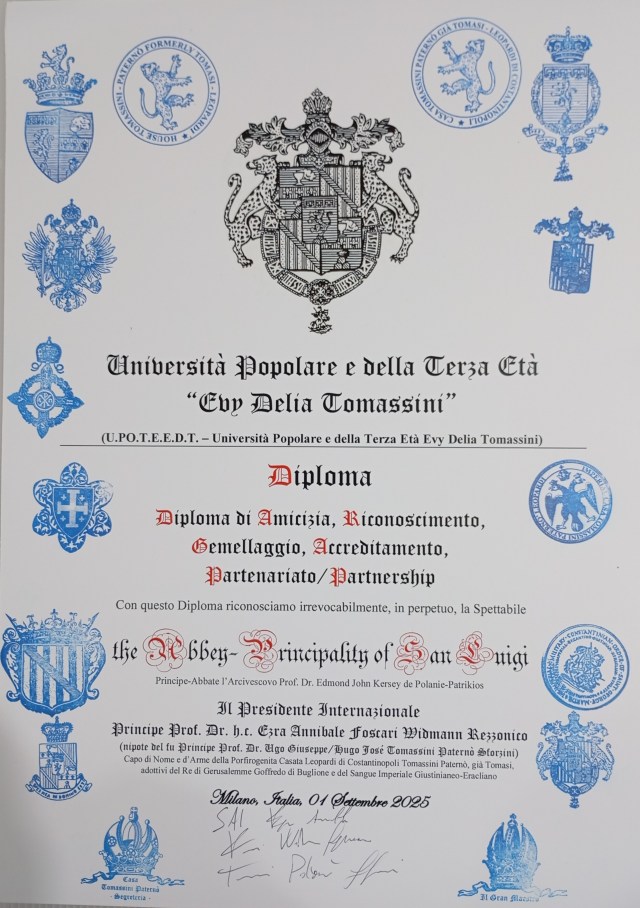

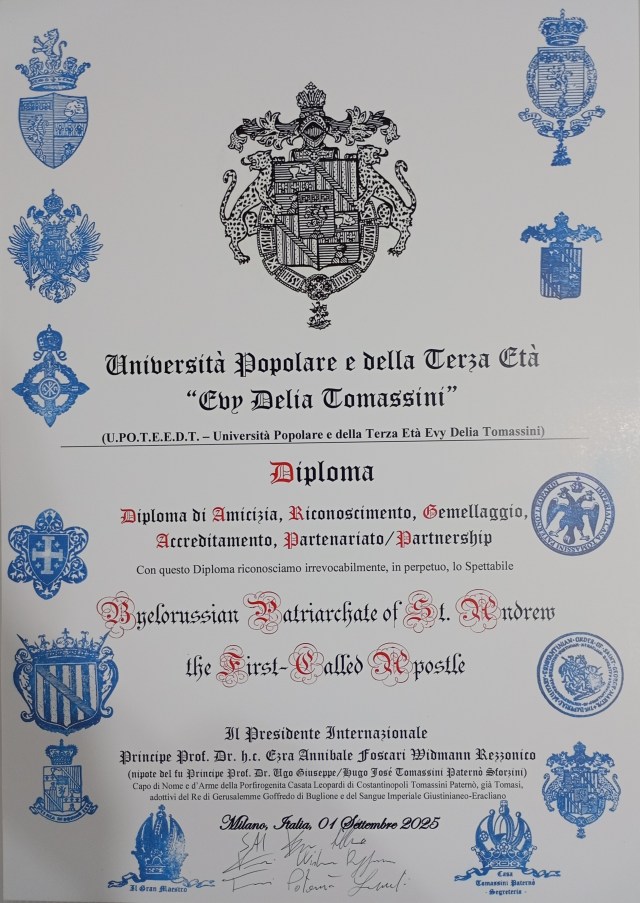

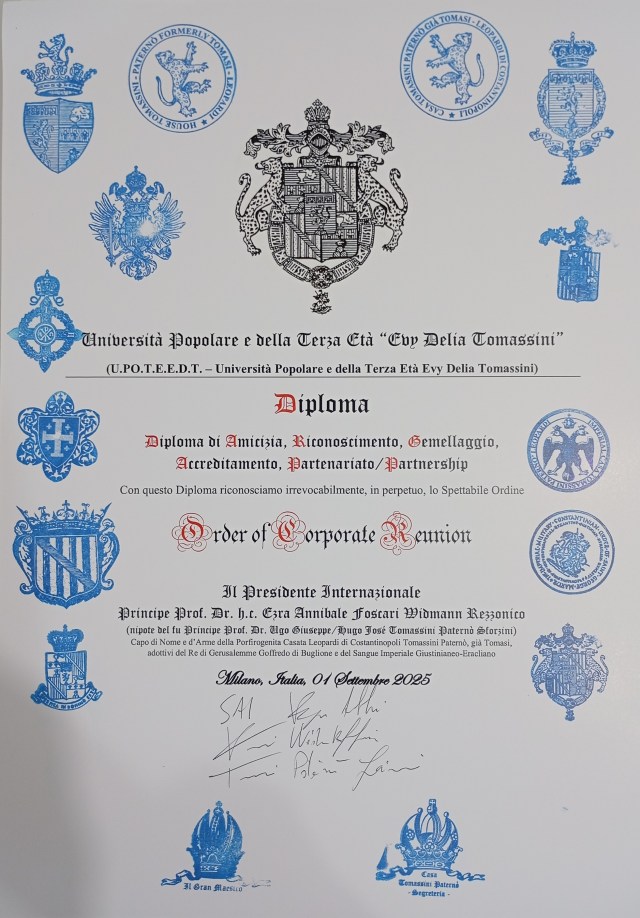

The Università Popolare e della Terza Età “Evy Delia Tommassini” is a private university after the model of the Italian “universities of the people”, and an institution of the Imperial House of Tommassini-Paterno of Constantinople, which is currently based in exile in Milan, Italy. The University has entered into a mutual full agreement of friendship, recognition, twinning, accreditation and partnership with the University.

The Università Popolare e della Terza Età “Evy Delia Tommassini” is a private university after the model of the Italian “universities of the people”, and an institution of the Imperial House of Tommassini-Paterno of Constantinople, which is currently based in exile in Milan, Italy. The University has entered into a mutual full agreement of friendship, recognition, twinning, accreditation and partnership with the University.

1. The Abbey-Principality of San Luigi

2. The Apostolic Episcopal Church

3. The Byelorussian Patriarchate of St Andrew the First-Called Apostle

3. The Apostolate of the Holy Wisdom and its constituent bodies

4. The Ecclesia Apostolica Divinorum Mysteriorum

5. The Order of Corporate Reunion

6. The Order of the Sacred Cup

The Most Revd. Michael Cuozzo, OCR, OFE, DD, STD, PhD, MA, has been appointed as Provincial of the West, USA, and Titular Archbishop of Epiphania in the Apostolic Episcopal Church, and as a Deputy to the Primate, and further in the Catholicate of the West as Patriarch of Malaga and Exarch for the USA. Archbishop Michael will be designated as Mar Francis.

The Most Revd. Michael Cuozzo, OCR, OFE, DD, STD, PhD, MA, has been appointed as Provincial of the West, USA, and Titular Archbishop of Epiphania in the Apostolic Episcopal Church, and as a Deputy to the Primate, and further in the Catholicate of the West as Patriarch of Malaga and Exarch for the USA. Archbishop Michael will be designated as Mar Francis.

He is Primate and Presiding Archbishop of the Order of Franciscans of the Eucharist (O.F.E.), a chartered religious order of the AEC incorporated in California that affirms its identity and unity as a Roman Catholic autocephalous body and takes particular inspiration from the life and example of Pope Francis.

The Prince-Abbot has received the Pilgrim of Hope certificate from the Archbishop of Cracow, Poland. The certificate recognizes his participation in the Jubilee Route (St Philomena’s Way) designated by the Pope for the Holy Year 2025. The Pilgrimage is recognized as an opportunity for a personal encounter with Jesus and to bring the message of Jesus to others. The certificate ends with a pastoral blessing. The award of this certificate further emphasises our unity with other Catholics and our common hope in our Lord and Saviour through the ancient and honoured path of pilgrimage.

The Abbey-Principality of San Luigi has entered into mutual agreements of partnership, accreditation and recognition with the Humanitarian Environmental Foundation, which is established as a nonprofit foundation in Las Vegas, Nevada, USA, under the presidency of Professor Pasquale Sorrentino. These agreements serve to further emphasise the commitment of the Abbey-Principality towards care for the environment.

The Abbey-Principality of San Luigi has entered into mutual agreements of partnership, accreditation and recognition with the Humanitarian Environmental Foundation, which is established as a nonprofit foundation in Las Vegas, Nevada, USA, under the presidency of Professor Pasquale Sorrentino. These agreements serve to further emphasise the commitment of the Abbey-Principality towards care for the environment.

Abbey-Principality of San Luigi

The Order of the Crown of Thorns

The Order of the Lion and the Black Cross

The Grand Prix Humanitaire de France et des Colonies

The Byzantine Order of Leo the Armenian

The Royal Order of the Imperial Crown of Byelorussia

The Order of the Golden Cross of Miensk

The Order of the Byzantine Cross

The Order of St Laurent

The Royal Order of Ivan the Infante

The Order of the Pedigree

The Order of Merit of Leszek II

The Royal Byelorussian Protectorate of the Orthodox Order of the Knights Hospitaller of St John of Jerusalem

The Royal Byelorussian Protectorate of the Military and Hospitaller Order of St Lazarus of Jerusalem

The Order of the Sacred Cup

The Apostolic Episcopal Church

The Byelorussian Patriarchate of St Andrew the First-Called Apostle

The Order of Antioch

The Order of Corporate Reunion

The Order of Ave Maria

The Order of S Teresa – The Little Flower

The Order of the Holy Wisdom

The Prefectory of Great Britain of the Confraternitas Oecumenica Sancti Sepulcri Hierosolymitani

The Ecclesia Apostolica Divinorum Mysteriorum

The International College of Arms of the Noblesse

The Institute of Arts and Letters (London)

The Regency of Lomar

The Belarus Monarchist Association

Requiem æternam dona ei, Domine

Et lux perpetua luceat ei

Requiescat in pace.

Amen.

The Abbey-Principality of San Luigi extends its sincere condolences on the death of Pope Francis. In 2020, Pope Francis bestowed the Apostolic Blessing upon the Prince-Abbot. Through all our ministry, and particularly that of the Order of Corporate Reunion, the Pope is looked upon as a centre for Christian unity and is always held in prayer, signifying that we remain one in Faith even though we are jurisdictionally separate from the Holy See.

You must be logged in to post a comment.